1. Finding Land

What is your vision?

Before you start on this adventure, ask yourself as an individual or collectively as a group, what type of land are you looking for? What are the needs of your community? Within walking distance of homes so its visible to the community? Or large enough to start a farm-sized operation?

Create a list of what you are looking for and consider:

• Type and scale of growing project - small community garden or large community supported agriculture project?

• Location

• Orientation

• Access

• Quality of Soil

• Relationship with neighbours

• What you are hoping to grow

Click here to view the COSS list of issues to consider when choosing a site, which includes appraisal of any buildings.

Howling for your pack: Finding others to make your vision a reality

Working with other people can be the make the difference between making something happen or not. In a group you have access to resources and energy that you can’t generate on your own - from contacts and skills, to spare time or that boost of enthusiasm you need.

When it comes to accessing land and convincing a landowner that your presence will be of benefit, having a well-organised group can make a difference.

You may find others who want to grow by:

• Tapping in to existing networks, such as local environment groups, WIs, Transition Groups and so forth. Check out our list of local networks in Somerset here.

• Put the call out - reach others by putting an advert, letter or article in the local newsletter, newspaper, shop noticeboard or website. Put posters up in your parish.

• One suggestion is to organise a public meeting, to get together everyone interested. You can advertise and say that you are looking for others to form an Awaiting Allotment Association. Invite local landowners and the community. You could also invite people to talk who have done it already and are an inspiring model. Invite a speaker from a national group (see a list of them here), or you could show a short film (see the Incredible Edible Somerset films here). A meeting like this could help generate enthusiasm for the project and convince any landowners present that the group has the skills and commitment to take the project forward.

Before you start - is there already provision for growing in your area?

Before starting to search for new land to bring into community food production you may wish to research:

• Are there allotments in your neighbourhood? Is there a waiting list?

• Is there a community garden nearby that could do with an injection of energy?

• You can find your nearest community growing project on the Somerset Community Food map

Starting to search

When starting to look for land it may be more useful for your group to start wider and then slowly filter through the different options.

In the Community Land Advisory Service guidance on finding land they list a number of potential ways to find suitable land:

- Physically walking around your local area

- Talking to local people with good local information

- Advertising that you are looking for land, for example:

Placing leaflets in your local library, leisure centre, community centre etc., saying you are looking for land to start a community growing project. If you are looking for farmland then agricultural stores are a good place to advertise.

Online through social networks like Facebook and Twitter e.g.

Somerset Community Food - newsletter or Facebook page or the Grow for Good Facebook group

You may also wish to:

- Advertise on local email lists, news sites and more

- Write a press release to get your search featured in local newspapers and magazines

- Use internet mapping tools such as Google Earth to identify undeveloped or open land within your search area.

- Use brokerage services that are detailed online, such as landshare, you may have a local community food organisation that may provide a similar service.

- Access documents from the local council office or website, these may include:

⁃ Plans and policies of the planning development, which may indicate potential future developments and opportunities

⁃ Their open space strategy - which should indicate all open space within the council area & as well as their strategies for future spaces

⁃ Allotment strategy - which may include potentially available allotments and the councils strategy for developing any future spaces e.g. Taunton Deane's District Council’s allotment strategy

- You may find land through a local estate agent, in office or online. You can also register your plans with them and if they are friendly and supportive they may notify you with any potential leads

- You could also contact other local businesses that regularly interact with landowners, such as architects.

- Public landowners may also have potential land available, potential organisations include:

⁃ Local Authorities

⁃ Local NHS Trusts

⁃ Local Housing Associations

⁃ The Forestry Commission

⁃ The National Trust

It may also be worth thinking of people who you can survey about their experiences, for example has a local parish council tried or previously advertised? Is there an experienced community gardener in your network? What did they learn and what can they share with you about their experiences to help you with your project?

In terms of potential spaces, the options are endless. You may consider:

• Village halls & adjacent land

• Playing fields - including edges & verges

• Schools

• Railways

• Hospital or GP surgeries

• Local mental health projects

• Churches

• Housing Associations

• National trust

Finding out who owns the land

If you do not know or are not sure who owns a piece of land, you could try the following:

- Asking neighbours of the land

- Posting a notice on the land to ask the landowner to get in touch

- Advertising your query through social media, local newspapers and other avenues in the looking for land section

- Contacting your local council. People you may wish to speak to include the Property Department, Rates Assessor and District Valuer

- Use the Land Registry’s Map Search

2. Approaching landowners

Before approaching a landowner it is worth preparing so that you can make your case effectively, ask yourselves:

1. What reasons will you give the landowner to convince them to support your project?

2. Why should they allow you to start?

3. What concerns are they likely to have and how can you reassure them?

4. How will your group come across - well organised with good intent?

5. What benefits can you list? e.g.

• Improving the appearance of the land

• Reducing or taking away the need for the landowner to maintain the land

• Financial benefits

• Security and safety improvements

Communicating with landowners

Some top tips for interacting with landowners, learnt from projects in our network:

- Be professional – just have 1-2 people as main contacts – to show that the group is serious, organised and competent

- Be fair about financial considerations – offer to cover any loss of single farm payment

- Be flexible - acknowledge the needs and concerns of the landowner and offer terms they can sign up to

- Show positive case studies from elsewhere

- Ensure you are always polite and friendly, but be assertive

- Make sure you have financial information with you

Making contact

Some groups write letters, however many have benefitted from making an appointment that gives them a chance to explain their ideas, focusing on the benefits. Meeting face to face is also the first step in building a relationship.

Approaching public landowners

Public landowners, such as the NHS or local authorities, have their own aims and objectives and ‘corporate social responsibility’. One of the best ways to access land from these landowners is to show:

• How you will positively address their aims & objectives

• This will be a low cost way of meeting their objectives

Once you have identified a plot and successfully communicated with a landowner, you will be ready to negotiate and get a written land agreement.

3. Evidencing demand & making your case

It is useful for your project, and for landowners, to demonstrate there is demand for what you are trying to do. For example, research allotment waiting list numbers via your local / parish council. The National Society of Allotment Leisure Gardeners suggest doubling this number to account for latent demand - all the people that haven’t put themselves on the waiting list, or get the buzz to start once a site opens.

If approaching local authorities there are several resources which you can quote or reference when making your case including:

• Local planning or open space (PPG17) amenity policies and strategies

• Sustainable Community Strategies and Neighbourhood plans

• You can also talk directly to developers if new housing is being planned in your area. 106 agreements and the new Community Infrastructure Levy can be used to acquire growing space (more Section 106 information here). Plus, Planning Aid have resources and email helpline offering advice.

• If you anticipate future demand, make sure that space for growing food features in new Local Development Frameworks for your area.

4. Leasing land - negotiation and legal agreements with the landowner

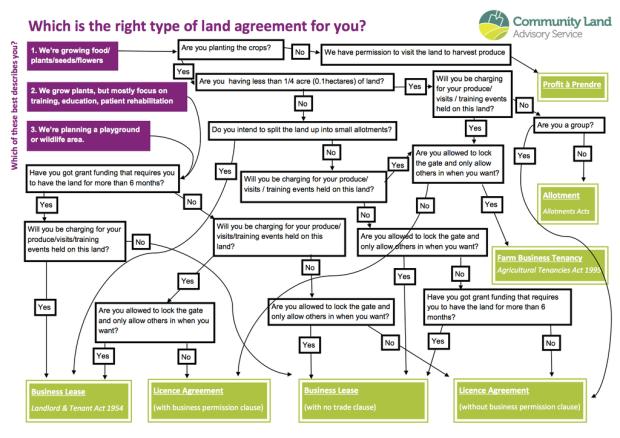

Social Farms and Gardens have produced a useful flowchart.

- Capture your project's aims and objectives

- Talk to the neighbours of the site, gain feedback on ideas and continue to build a positive relationship as activities may affect them.

- Begin to complete the Heads of Terms to start to formalise your plans - download the Community Land Advisory Service template here.

- Discuss insurance with the landowner, you will need to provide public liability cover.

- Check what type of legal agreement is appropriate - see the flowchart produced by the Community Land Advisory Service below:

Now you will need to get the paperwork in place to ensure all parties are happy and in agreement on how the land should be used.

- Amend/ Negotiate Heads of Terms with the landowner. If necessary seek advice from a third party to help facilitate the process.

- With the landowner work out the legal agreement details including a template lease (see Guidebook for Landowners for information on leases and licences).

- Take legal advice to ensure you are using the right agreement with all necessary clauses. A solicitor should be instructed to finalise the agreement.

- Then, exchange the draft agreement. If both are happy print the final copy, complete notices, sign and exchange.

5. Buying Land

Buying land as a community group is increasingly attractive option for groups that wish to have more permanence and connection to place and a greater ability to make decisions about land use and access.

Some of the reasons you may wish to buy land:

• It can feel different to ‘own’ land - creating belonging & a greater sense of connection

• There is a greater feeling of independence & freedom

• Longer term security allows for investment of time & energy into longer-term projects, such as planting trees or erecting buildings.

• If bought outright there is no rent to pay.

• Buying land allows control of decisions about what land is used for and by whom. This is great for more alternative/pioneering forms of land use such as permaculture & agroecology.

• Buying land as a group can bring people together. It can take a lot of effort and shared responsibility to buy land so can really strengthen a group.

• Grant funders will often want long-term land security and longer tenancies, and so a group that owns land can be more attractive.

• Sources of income that are available for buying land may not be so for renting. For example crowd fundraising, certain grants, contributions from the public and others in a community may all be more likely if people are grouping together to buy land.

• Buying land means community groups will have a valuable asset that a group can then borrow against the value. A group could also generate an income from renting land.

• More than anything, buying land may mean more security and self determination for a community aiming to feed themselves.

Some of the reasons you may not:

• Cost! Land is becoming increasingly expensive, especially where compared to the cost of renting. If renting of a benevolent landowner, costs may be significantly cheaper. The value of land can be massively inflated also due to competition for development, making it prohibitive for many grassroots groups.

• It can be quite difficult to find suitable land to buy. Factors such as size, location and topography, especially in relation to food growing, are important and finding suitable land can be challenging. Land is often not always advertised or easy to find out about.

• The group buying the land must be willing, and able, to take responsibility for some long term serious and complicated issues, such as protecting investors’ money and undertaking the legal duties of landowners.

• Failure by poorly run groups might diminish confidence in other community groups.

• Many groups and projects are often informal, grassroots and temporary and do not need to buy land.

• Groups need to be fairly solid, responsible and consistent to manage land over a long time. It can also be fairly difficult to move to another site if a group’s needs change.

• Buying land is often easier in areas of privilege. Raising funds in different areas will need awareness about class and access. ‘Owners’ and people who have not contributed may feel a hierarchy, even if access rights are the same.

• Buying land does carry financial risk. In some cases, people will risk their savings to buy land, for example when buying withdrawable shares. Without a solid plan there is also potential for conflict.

• There are up front costs to buying land that will not be recouped if a sale falls through, such as surveying.

• If appropriate ownership models are not established in the beginning there may be tax problems.

• Timing! Often there are very short windows of time from when land becomes available for purchase.

• Groups need to have access to appropriate skills e.g. Legal knowledge, accountancy, and finding the right mix of people with different skill sets can be challenging.

• Where a community purchases land from a public body (e.g. local authority) this can be a form of privatisation, resulting in the land effectively being less accessible; however, where a community group purchases land from a private owner, this makes the land more accessible.

• We can not automatically assume that community land ownership will result in the land being well cared for e.g. if a group purchases 20acres without knowledge/ experience of how to manage it. Having a solid skill set and experience within a group around managing land is important.

Further resources & links

• Community Land Advisory Service

• Biodynamic Land Trust

• Information on Community Shares

• Ecological Land Cooperative

• Soil Association Land Trust

• Wessex Community Assets

Inspiring examples:

• Plotgate Community Farm & Plotgate Land Trust

• Stroud CSA

• Whistlewood Common, Derbyshire

Planning

We’d like to thanks Planning Aid, whose workshop provided a basis for this summary.

Planning Permission

Planning permission is required for works or a change of use amounting to ‘development’.

‘Development’ includes many types of building work - some of which may be undertaken as part of food growing projects. It also includes the change of use of a building or land from one use to another; which could impact on certain projects.

Some minor works are granted planning permission automatically if they meet certain criteria, avoiding the need to make a formal planning application. Work falling into this category is called ‘permitted development’.

A piece of land (or building) will have a legal planning use - either permitted by a planning permission, or acquired because it's been used for that purpose for a certain time period. If land is used for a purpose other than its legal planning use, that may amount to a ‘change of use’ requiring planning permission.

Most groups growing food will either be using agricultural land, or land within gardens.

What is ‘Agriculture’ as defined in planning law?

‘Agriculture’ is defined at section 336 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 as including “horticulture, fruit growing, seed growing, dairy farming; the breeding and keeping of livestock (including any creature kept for production of food, wool, skins or fur for the purpose of its use in the farming of land); the use of land as grazing land, meadow land, osier land, market gardens or nursery grounds; and the use of land for woodlands where that use is ancillary to the farming of land for other agricultural purposes”

Points to remember about planning

- Planning is not always black and white however, and there are many other factors to consider beyond whether land is clearly used for agricultural purposes.

- Decisions about whether something requires planning permission can sometimes even come down to judgement and interpretation. Different councils, and even different Officers can reach different views about the same information.

- The main point to remember is don’t assume anything!

Getting advice

The best advice about planning is to get advice:

• Make an appointment to see a District Council Planning Officer

• Contact an organisation like Planning Aid

• Chapter 7 - about low impact development

When seeking advice it's good to prepare for the meeting:

• Any sketches, maps, draft designs and layouts

• Photos

• Any questions you have

• Have clarity over your intended use

• Key issues

During the meeting try to establish whether the proposal is likely to be acceptable in principle, or not. If it isn’t ask why not and what, if anything, would make it acceptable.

Make sure you write down what the planner says. If permission is not likely to be required, ask the Planning Officer if they could put this in writing for you.

Making a Planning Application

Anyone can make a planning application in respect of any piece of land or building. You do not need to own the land or building. If you don’t own the land, you should confirm that the landowner is happy for your project to proceed if and when the necessary planning permission is in place.

A planning application needs to be accompanied by a completed, ownership certificate, plans and application fee. A design and access statement may be required too, and other surveys of documents may also be required in some cases.

Once the Council has registered the application, you will receive a letter advising you which Planning Officer is dealing with the application and the target date for the decision. Most minor applications take up to 8 weeks to be considered.

Once the decision has been made, a printed decision notice will be issued by the authority. If the application as been approved, it may well be subject to conditions. Make sure you read these carefully.

If the planning application is refused, the decision notice will set out the reasons why. If the authority’s concerns can be overcome by amending the proposal in some way, it may be worth submitting a revised proposal - and often no application fee is required for this re-submission.

If however, a revised proposal would not overcome the authority’s concerns, of if you do not agree with the reason given for refusing the application, it is open to you to appeal against the decision. Appeals are considered by the Planning Inspectorate, a body entirely independent of local authority that originally considered the application.

Don’t go through the process alone! Many others in Somerset have been through the planning process themselves and can share their experiences and tips. Local networks of people can also write supporting statements and organisations, such as Somerset Community Food, are very often willing to write letters of support for food-related projects.

Further contacts & resources

• Your Local Authority - Somerset Council

• The Planning Portal

• The Planning Inspectorate

• HogCo Planning Toolkit - Planning Matters

• Community Land Advisory Services’ Planning Reform Advisory Document (download here)

Originally written by Nicole Vosper, with financial support from the Somerset Land and Food Project, supported by the Big Lottery and updated 2023.

For any contributions, suggestions for improvement, resources and more please email info@somersetcommunityfood.org.uk